By Alexa James

Times Herald-Record May 13, 2007

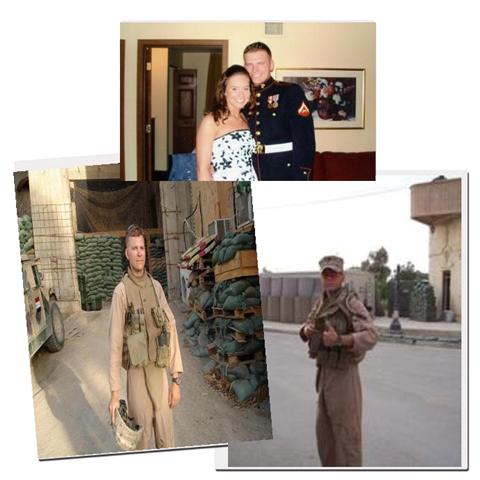

Times Herald-Record Reporter Alexa James has spent more than six months following the Siruchek family as they await the return of their son and brother, Matt, from service in Iraq. He is scheduled to return to the United States this month. The family has struggled with the heart-wrenching emotions of having a loved one in harm’s way. These are portraits of that story.

The father: September 2006

Speeding south down Interstate 95, Adam Siruchek glances sideways at his son sleeping in the passenger seat. He reaches over, pats his leg.

Not to wake him. Just to feel the knee. Squeeze it. Remember it.

Over 11 hours, across some 650 miles, Adam wills himself to memorize such details as father and son make their way from the Village of Walden to the military metropolis of Jacksonville, N.C.

Once there, at Camp Lejeune, base to the world's largest concentration of Marines and sailors, a dad will have a short time to cement 20 years worth of son into his memory.

Raising Matthew Siruchek was a turbulent ride. Bullheaded and needling, Adam's oldest boy was fiercely independent. Push Matt in the right direction, and he'd shove back, harder.

The U.S. Navy had squared his son's stubborn streak, much as it had for Adam, now 44, a quarter-century ago. The world was a different place then.

Adam wanted his son to stay "blue side," serving his time stateside or aboard a ship "and wearing dungarees and a white hat and floating in the middle of the ocean somewhere."

Matt, the hardhead, went "green side" instead. He became a Navy hospital corpsman, a medic, assigned to look after the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment in Iraq. In the name of Operation Iraqi Freedom, they were headed to Ramadi, capital of the Anbar province, a city on the southwest corner of the Sunni Triangle, about 30 miles west of Fallujah. Ramadi street graffiti had tagged it the "graveyard of the Americans."

"If you wanted to get into the middle of it," Adam sighs, "that's the way to do it."

The deployment leads Adam through a minefield of questions. "Is this something that can be won? You know, this war on terror? Terror has been around for years and years," he says. "Are we making a difference?"

At least his son would be saving lives, he bargains with himself, not just taking them.

But this car ride, the last one before Iraq, can't be wasted on unknowns. Quickly, before it's time to say goodbye, a father and son must square away their past.

By the time Adam leaves the base, Matt has already changed into Marine Corps fatigues.

Adam tries to burn it all into his memory, to have it ready if he needs to recall it later.

"We'd had our share of turbulent times," he says. "I needed to make sure we were right with that. That all was forgiven."

Adam swallows hard.

He continues when it's safe. "Sometimes, I'll be driving around and I'll still see him sleeping in the car." He'll reach over and pat the empty seat.

"It's a great memory. Keeps me going."

The brother: December 2006

Erik Siruchek has heard it a hundred times. "You look just like your brother."

Matt Siruchek graduated and took off for Navy boot camp two years ago. Erik is 17 now and wrapping up his junior year at Valley Central High. Still, he is better known to his teachers as "Matt," or, if he's lucky, "Matt's little brother."

And that's fine. Erik thinks he'll probably go military, too. Special forces, he says, because he's "good at that military sneaking around stuff."

Most of Erik's life, it seems, has been lived on his big brother's terms. Sports, classes, girls: "I got my dad, but we don't really talk much about girls," he says. "Matt was the one I went to."

Matt taught Erik how to drive stick on his black convertible. "He used to make me start it on the hill in the driveway."

When he deployed, Matt told Erik to start it now and then, keep it running. One day, he told him he could take it to the prom. Erik declined. "If something happened to it he'd kill me."

It's not as if Matt doesn't trust Erik. Last summer, he often took him rock climbing on the Shawangunk Ridge. If he tried something risky, he'd make Erik stand by to brace the ropes. Erik would sweat bullets.

Since the deployment, Matt's requests have intensified. First came the wedding proposal. Erik was the first to know Matt's plans with his high school sweetheart. "We kind of shook hands," Erik recalls, "then he told me to work on my best man's speech and to look after his girl."

He also made Erik promise to spare him no bad news from the home front. "He gave me this whole speech about how even if everyone else doesn't tell him stuff, he wants me to tell him."

In time, Erik would have to tell Matt about Mom not feeling well, about Dad's new job, his sister's car crash. Everything.

The toughest demand came just before New Year's, when Matt asked Erik to go to Arlington National Cemetery.

A medic from Matt's Fleet Marine Force had died. Navy Hospital Corpsman Christopher Anderson, 24, from Colorado, was killed in a mortar attack Dec. 4.

Matt took it hard. "That kid, he pretty much kept Matt sane," Erik said. "He was his best friend."

Thirty Navy medics have died in Iraq and Afghanistan since September 2001, accounting for nearly 30 percent of Navy casualties.

The only members of Anderson's unit who could attend his funeral were those the medic had saved during his tour. Marines who had been sent home to heal showed up to say thanks to their "doc."

In section 60 of the 600-acre cemetery, Erik saw a Marine, missing both legs and one hand, offer condolences to the family. He saw snow-white gloves fold tight an American flag, heard the rifles crack and the bugle sound.

"I was OK for a while," he said, until the medic's brother approached the coffin. Erik lost it. After the funeral, after the somber crowd had wandered off, the brother was still standing there.

"Oh crap," Erik thought, "What if that's me next month?"

The sisters: February 2007

The Siruchek siblings are gathered in mom's living room, spilling popcorn, surfing MySpace, getting on and off their cells and trying to get the VCR to work.

"We're gonna miss Justin!" groans sister Jessica North, 23. The Grammy Awards are on tonight, and pop-throb Justin Timberlake will perform some hit single called "SexyBack." Jess "loves" Justin.

But the Grammy's are on at the same time as the season premier of "War Stories." The Fox News documentary tracks Lt. Colonel-turned-correspondent Oliver North, embedded in Ramadi with the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment — these are Matt's Marines.

The girls get e-mail from Matt and the occasional phone call, but tonight they surround the TV in the hope that maybe, with any luck, he'll flash across the screen. Maybe that "pain-in-the-ass" brother, who they miss terribly now that he's thousands of miles away in one of the scariest places on Earth, will land himself a spot on national TV.

Of course, the VCR won't work, so Mom improvises. She sets up a camcorder to record the TV screen. Jessica abandons Justin.

"Justin will be up on YouTube tonight anyway," says little sister Sharon Siruchek, 18, signing onto AOL Instant Messenger to see if Matt's signed on in Iraq.

Families of soldiers in Iraq have unprecedented access to their deployed loved ones. Skirting official military channels, they can e-mail, text-message and post pictures and videos on any number of online social venues, such as MySpace.

That's how the girls found out about "War Stories." Matt had operated on a cameraman's ingrown toenail and posted some pictures of the procedure online. Fox news posted the same shots on their site, and later e-mailed Matt's mom.

"Not only can your son cut away an evil toenail," wrote cameraman Mal James, "he has the voice of an angel." James said he filmed Matt playing guitar and singing "Silent Night" at a church Christmas service in the barracks. Maybe that would make tonight's episode.

Fifteen minutes in, the show cuts to the mess hall and row after row of olive T-shirts hunched over trays of chow. On the left, one of the crew cuts looks up at the camera and smirks. It's just a second or two before the camera cuts away, but it's enough.

"There he is!" the girls squeal in unison. "Oh my God! That's Matt! That's his head!

Immediately, the laptop and the cell phones are flashing and beeping with text messages from friends watching around town. The girls work themselves into a frenzy. When "War Stories" cuts to a commercial, they flip back to the Grammys.

Justin Timberlake is halfway through his set.

The following week, Sharon is playing on her computer when she gets a disturbing text message from Matt:

"Hey, I got shot. lol."

The mother: May 2007

When she sleeps at all, Becky Siruchek sleeps with her cell phone. "Just in case."

In case her son calls again at 2 a.m. to tell her he's been shot.

"Don't worry," he told her. "I've been cut worse shaving."

Matt had been outside on a satellite phone with his fiancee when he heard the crack.

A sniper in an abandoned factory some 90 yards away fired on the medic. The bullet ricocheted into his stomach. He saved the 7.62 mm slug to show her.

"Just a couple of stitches and a Band-Aid." he said. "They told me to call you to say that I'm all right."

Becky was not. She had nightmares, lost her nerve in line at the grocery store, couldn't focus at work. The kids would ask her if she was OK and she'd scream, "My child was hit with a bullet! No! I'm not OK!"

But the rest of the world went on. Sharon was in a car accident and spent a few days in the hospital. Erik had play practice every night and was struggling in chemistry. Becky was falling behind in her night school classes too.

And all the while, on the news, Republicans rambled on about extended deployments, Democrats countered for withdrawals, the Defense Department begged for billions of dollars and soldiers kept blowing up.

"I feel like I've aged a decade in the last six months," Becky says. "It's the anticipatory grief, living in expectation or fear of a loss. Now I feel extra tension because we're in the homestretch."

Matt is due home this month. He's already started shipping stuff back: a flight suit, a guitar amp, DVDs and books. "Here's my little piece of Iraq," says Becky, holding up a medicine bottle filled with sand.

"I just want him out of there."

And then what?

Matt won't be the same. He's spent seven months holding pressure to bleeding bodies, plucking shrapnel, stitching flesh back together. He treats the coalition forces, and sometimes, he treats the insurgents.

"He hasn't had a solid night's sleep since he left," Becky says. "I know he's not eating right." On the phone, Matt sounds tired and beat, says he's sick of it all.

The joy of his homecoming brings with it an undercurrent of new fears, namely post-traumatic stress syndrome. Will Matt be OK? Can he be happy?

Other military families have tried to prepare the Sirucheks, tell them what to watch for.

"I'm scared I'm not going to have the same brother," says Erik, "at least not for a while, if ever. I'm scared he's not going to want to do anything with me."

The Sirucheks have a block of rooms reserved outside Camp Lejeune, N.C.

Teachers and bosses have been put on notice. The last time they talked, Matt said his unit would be shipping out of Ramadi in days. He should be back in the States by Memorial Day weekend.

He told his dad to bring the black convertible.

A family's struggle to stay the course while one of their own is off in Iraq

Monday, May 14, 2007

Monday, May 7, 2007

Graduation

Saturday, April 28, 2007

Uneasy Alliance Is Taming One Insurgent Bastion

By KIRK SEMPLE

Published: April 29, 2007

ON THE JOB TOGETHER Iraqi policemen and American troops patrol near Ramadi in Anbar. Ramadi’s police force has sharply increased in the past year.

RAMADI, Iraq — Anbar Province, long the lawless heartland of the tenacious Sunni Arab resistance, is undergoing a surprising transformation. Violence is ebbing in many areas, shops and schools are reopening, police forces are growing and the insurgency appears to be in retreat.

“Many people are challenging the insurgents,” said the governor of Anbar, Maamoon S. Rahid, though he quickly added, “We know we haven’t eliminated the threat 100 percent.”

Many Sunni tribal leaders, once openly hostile to the American presence, have formed a united front with American and Iraqi government forces against Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia. With the tribal leaders’ encouragement, thousands of local residents have joined the police force. About 10,000 police officers are now in Anbar, up from several thousand a year ago. During the same period, the police force here in Ramadi, the provincial capital, has grown from fewer than 200 to about 4,500, American military officials say.

At the same time, American and Iraqi forces have been conducting sweeps of insurgent strongholds, particularly in and around Ramadi, leaving behind a network of police stations and military garrisons, a strategy that is also being used in Baghdad, Iraq’s capital, as part of its new security plan.

Yet for all the indications of a heartening turnaround in Anbar, the situation, as it appeared during more than a week spent with American troops in Ramadi and Falluja in early April, is at best uneasy and fragile.

Municipal services remain a wreck; local governments, while reviving, are still barely functioning; and years of fighting have damaged much of Ramadi.

The insurgency in Anbar — a mix of Islamic militants, former Baathists and recalcitrant tribesmen — still thrives among the province’s overwhelmingly Sunni population, killing American and Iraqi security forces and civilians alike. [This was underscored by three suicide car-bomb attacks in Ramadi on April 23 and 24, in which at least 15 people were killed and 47 were wounded, American officials said.]

Furthermore, some American officials readily acknowledge that they have entered an uncertain marriage of convenience with the tribes, some of whom were themselves involved in the insurgency, to one extent or another. American officials are also negotiating with elements of the 1920 Revolution Brigades, a leading insurgent group in Anbar, to join their fight against Al Qaeda.

These sudden changes have raised questions about the ultimate loyalties of the United States’ new allies. “One day they’re laying I.E.D.’s, the next they’re police collecting a pay check,” said Lt. Thomas R. Mackesy, an adviser to an Iraqi Army unit in Juwayba, east of Ramadi, referring to improvised explosive devices.

And it remains unclear whether any of the gains in Anbar will transfer to other troubled areas of Iraq — like Baghdad, Diyala Province, Mosul and Kirkuk, where violence rages and the ethnic and sectarian landscape is far more complicated.

Still, the progress has inspired an optimism in the American command that, among some officials, borders on giddiness. It comes after years of fruitless efforts to drive a wedge between moderate resistance fighters and those, like Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, who seem beyond compromise.

“There are some people who would say we’ve won the war out here,” said Col. John. A. Koenig, a planning officer for the Marines who oversees governing and economic development issues in Anbar. “I’m cautiously optimistic as we’re going forward.”

A New Calm

For most of the past few years, the Government Center in downtown Ramadi, the seat of the provincial government, was under near-continual siege by insurgents, who reduced it to little more than a bullet-ridden bunker of broken concrete, sandbags and trapped marines. Entering meant sprinting from an armored vehicle to the front door of the building to evade snipers’ bullets.

Now, however, the compound and nearby buildings are being renovated to create offices for the provincial administration, council and governor. Hotels are being built next door for the waves of visitors the government expects once it is back in business.

On the roof of the main building, Capt. Jason Arthaud, commander of Company B, First Battalion, Sixth Marines, said the building had taken no sniper fire since November. “Just hours of peace and quiet,” he deadpanned. “And boredom.”

Violence has fallen swiftly throughout Ramadi and its sprawling rural environs, residents and American and Iraqi officials said. Last summer, the American military recorded as many as 25 violent acts a day in the Ramadi region, ranging from shootings and kidnappings to roadside bombs and suicide attacks. In the past several weeks, the average has dropped to four acts of violence a day, American military officials said.

On a recent morning, American and Iraqi troops, accompanied by several police officers, went on a foot patrol through a market in the Malaab neighborhood of Ramadi. Only a couple of months ago, American and Iraqi forces would enter the area only in armored vehicles. People stopped and stared. The sight of police and military forces in the area, particularly on foot, was still novel.

The new calm is eerie and unsettling, particularly for anyone who knew the city even several months ago.

“The complete change from night to day gives me pause,” said Capt. Brice Cooper, 26, executive officer of Company B, First Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, First Infantry Division, which has been stationed in the city and its outskirts since last summer. “A month and a half ago we were getting shot up. Now we’re doing civil affairs work.”

A Moderate Front

The turnabout began last September, when a federation of tribes in the Ramadi area came together as the Anbar Salvation Council to oppose the fundamentalist militants of Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia.

Among the council’s founders were members of the Abu Ali Jassem tribe, based in a rural area of northern Ramadi. The tribe’s leader, Sheik Tahir Sabbar Badawie, said in a recent interview that members of his tribe had fought in the insurgency that kept the Americans pinned down on their bases in Anbar for most of the last four years.

“If your country was occupied by Iraq, would you fight?” he asked, smiling knowingly. “Enough said.”

But while the anti-American sheiks in Anbar and Al Qaeda both opposed the Americans, their goals were different. The sheiks were part of a relatively moderate front that sought to drive the Americans out of Iraq; some were also fighting to restore Sunni Arab power. But Al Qaeda wanted to go even further and impose a fundamentalist Islamic state in Anbar, a plan that many of the sheiks did not share.

Al Qaeda’s fighters began to use killing, intimidation and financial coercion to divide the tribes and win support for their agenda. They killed about 210 people in the Abu Ali Jassem tribe alone and kidnapped others, demanding ransoms as high as $65,000 per person, Sheik Badawie said.

For all the sheiks’ hostility toward the Americans, they realized that they had a bigger enemy, or at least one that needed to be fought first, as a matter of survival.

The council sought financial and military support from the Iraqi and American governments. In return the sheiks volunteered hundreds of tribesmen for duty as police officers and agreed to allow the construction of joint American-Iraqi police and military outposts throughout their tribal territories.

A similar dynamic is playing out elsewhere in Anbar, a desert region the size of New York State that stretches west of Baghdad to the Syrian and Jordanian borders. Tribal cooperation with the American and Iraqi commands has led to expanded police forces in the cities of Husayba, Hit, Rutba, Baghdadi and Falluja, officials say.

With the help of the Anbar sheiks, the military equation immediately became simpler for the Americans in Ramadi. The number of enemies they faced suddenly diminished, American and Iraqi officials said. They were able to move more freely through large areas. With the addition of the tribal recruits, the Americans had enough troops to build and operate garrisons in areas they cleared, many of which had never seen any government security presence before.

And the Americans were now fighting alongside people with a deep knowledge of the local population and terrain, and with a sense of duty, vengeance and righteousness.

“We know this area, we know the best way to talk to the people and get information from them,” said Capt. Hussein Abd Nusaif, a police commander in a neighborhood in western Ramadi, who carries a Kalashnikov with an Al Capone-style “snail drum” magazine. “We are not afraid of Al Qaeda. We will fight them anywhere and anytime.”

Beginning last summer and continuing through March, the American-led joint forces pressed into the city, block by block, and swept the farmlands on the city’s outskirts. In many places the troops met fierce resistance. Scores of American and Iraqi security troops were killed or wounded.

The Ramadi region is essentially a police state now, with some 6,000 American troops, 4,000 Iraqi soldiers, 4,500 Iraqi police officers and an auxiliary police force of 2,000, all local tribesmen, known as the Provincial Security Force. The security forces are garrisoned in more than 65 police stations, military bases and joint American-Iraqi combat outposts, up from no more than 10 a year ago. The population of the city is officially about 400,000, though the current number appears to be much lower.

To help control the flow of traffic and forestall attacks, the American military has installed an elaborate system of barricades and checkpoints. In some of the enclaves created by this system, which American commanders frequently call “gated communities,” no vehicles except bicycles and pushcarts are allowed for fear of car bombs.

American commanders see the progress in Anbar as a bellwether for the rest of country. “One of the things I worry about in Baghdad is we won’t have the time to do the same kind of thing,” Lt. Gen. Raymond T. Odierno, commander of day-to-day war operations in Iraq, said in an interview here.

Yet the fact that Anbar is almost entirely Sunni and not riven by the same sectarian feuds as other violent places, like Baghdad and Diyala Province, has helped to establish order. Elsewhere, security forces are largely Shiite and are perceived by many Sunnis as part of the problem. In Anbar, however, the new police force reflects the homogeneous face of the province and, most critically, appears to enjoy the support of the vast majority of the people.

A Growing Police Force

Military commanders say they cannot completely account for the whereabouts of the insurgency. They say they believe that many guerrillas have been killed, while others have gone underground, laid down their arms or migrated to other parts of Anbar, particularly the corridor between Ramadi and Falluja, the town of Karma north of Falluja and the sprawling rural zones around Falluja, including Zaidon and Amariyat al-Falluja on the banks of the Euphrates River. American forces come under attack in these areas every day.

Still other guerrillas, the commanders acknowledge, have joined the police force, sneaking through a vetting procedure that is set up to catch only known suspects. Many insurgents “are fighting for a different side now,” said Brig. Gen. Mark Gurganus, commander of ground forces in Anbar. “I think that’s where the majority have gone.”

But American commanders say they are not particularly worried about infiltrators among the new recruits. Many of the former insurgents now in the police, they say, were probably low-level operatives who were mainly in it for the money and did relatively menial tasks, like planting roadside bombs.

The speed of the buildup has led to other problems. Hiring has outpaced the building of police academies, meaning that many new officers have been deployed with little or no training. Without enough uniforms, many new officers patrol in civilian clothes, some with their heads wrapped in scarves or covered in balaclavas to conceal their identities. They look no different than the insurgents shown in mujahedeen videos.

Commanders seem to regard these issues as a necessary cost of quickly building a police force in a political environment that is, in the words of Colonel Koenig, “sort of like looking through smoke.” The police force, they say, has been the most critical component of the new security plan in Anbar Province and the key to sustaining the military successes.

Yet, oversight of the police forces by American forces and the central Iraqi government is weak, leaving open the possibility that some local leaders are using newly armed tribal members as their personal death squads to settle old scores.

Several American officers who work with the Iraqi police said a lot of police work was conducted out of their view, particularly at night. “It’s like the Mafia,” one American soldier at an outpost in Juwayba said.

General Odierno said, “We have to watch them very closely to make sure we’re not forming militias.”

But there is a new sense of commitment by the police, American and Iraqi officials say, in part because they are patrolling their own neighborhoods. Many were motivated to join after they or their communities were attacked by Al Qaeda, and their successes have made them an even greater target of insurgent car bombs and suicide attacks.

Abd Muhammad Khalaf, 28, a policeman in the Jazeera district on Ramadi’s northern edge, is typical. He joined the police after Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia killed two of his brothers, he said. “I will die when God wills it,” he said. “But before I die, I will support my friends and kill some terrorists.”

The Tasks Ahead

Some tribal leaders now working with the Americans say they harbor deep resentment toward the Shiite-led administration of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, accusing it of pursuing a sectarian agenda. Yet they also say they are invested in the democratic process now.

After boycotting the national elections in 2005, many are now planning to participate in the next round of provincial elections, which have yet to be scheduled, as a way to build on the political and military gains they have made in recent months.

“Since I was a little boy, I have seen nothing but warfare — against the Kurds, Iranians, Kuwait, the Americans,” Sheik Badawie, the tribal leader, said. “We are tired of war. We are going to fight through the ballot box.”

Already, tribal leaders are participating in local councils that have been formed recently throughout the Ramadi area under the guidance of the American military.

Iraqi and American officials say the sheiks’ embrace of representative government reflects the new realities of power in Anbar. “Out here it’s been, ‘Who can defend his people?’ ” said Brig. Gen. John R. Allen, deputy commanding general of coalition forces in Anbar. “After the war it’s, ‘Who was able to reconstruct?’ ”

Indeed, American and Iraqi officials say that to hold on to the security gains and the public’s support, they must provide services to residents in areas they have tamed.

But successful development, they argue, will depend on closing the divide between the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad, which has long ignored the province, and the local leadership in Anbar, which has long tried to remain independent from the capital. If that fails, they say, the Iraqi and American governments may have helped to organize and arm a potent enemy.

Uneasy Alliance Is Taming One Insurgent Bastion

Published: April 29, 2007

ON THE JOB TOGETHER Iraqi policemen and American troops patrol near Ramadi in Anbar. Ramadi’s police force has sharply increased in the past year.

RAMADI, Iraq — Anbar Province, long the lawless heartland of the tenacious Sunni Arab resistance, is undergoing a surprising transformation. Violence is ebbing in many areas, shops and schools are reopening, police forces are growing and the insurgency appears to be in retreat.

“Many people are challenging the insurgents,” said the governor of Anbar, Maamoon S. Rahid, though he quickly added, “We know we haven’t eliminated the threat 100 percent.”

Many Sunni tribal leaders, once openly hostile to the American presence, have formed a united front with American and Iraqi government forces against Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia. With the tribal leaders’ encouragement, thousands of local residents have joined the police force. About 10,000 police officers are now in Anbar, up from several thousand a year ago. During the same period, the police force here in Ramadi, the provincial capital, has grown from fewer than 200 to about 4,500, American military officials say.

At the same time, American and Iraqi forces have been conducting sweeps of insurgent strongholds, particularly in and around Ramadi, leaving behind a network of police stations and military garrisons, a strategy that is also being used in Baghdad, Iraq’s capital, as part of its new security plan.

Yet for all the indications of a heartening turnaround in Anbar, the situation, as it appeared during more than a week spent with American troops in Ramadi and Falluja in early April, is at best uneasy and fragile.

Municipal services remain a wreck; local governments, while reviving, are still barely functioning; and years of fighting have damaged much of Ramadi.

The insurgency in Anbar — a mix of Islamic militants, former Baathists and recalcitrant tribesmen — still thrives among the province’s overwhelmingly Sunni population, killing American and Iraqi security forces and civilians alike. [This was underscored by three suicide car-bomb attacks in Ramadi on April 23 and 24, in which at least 15 people were killed and 47 were wounded, American officials said.]

Furthermore, some American officials readily acknowledge that they have entered an uncertain marriage of convenience with the tribes, some of whom were themselves involved in the insurgency, to one extent or another. American officials are also negotiating with elements of the 1920 Revolution Brigades, a leading insurgent group in Anbar, to join their fight against Al Qaeda.

These sudden changes have raised questions about the ultimate loyalties of the United States’ new allies. “One day they’re laying I.E.D.’s, the next they’re police collecting a pay check,” said Lt. Thomas R. Mackesy, an adviser to an Iraqi Army unit in Juwayba, east of Ramadi, referring to improvised explosive devices.

And it remains unclear whether any of the gains in Anbar will transfer to other troubled areas of Iraq — like Baghdad, Diyala Province, Mosul and Kirkuk, where violence rages and the ethnic and sectarian landscape is far more complicated.

Still, the progress has inspired an optimism in the American command that, among some officials, borders on giddiness. It comes after years of fruitless efforts to drive a wedge between moderate resistance fighters and those, like Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, who seem beyond compromise.

“There are some people who would say we’ve won the war out here,” said Col. John. A. Koenig, a planning officer for the Marines who oversees governing and economic development issues in Anbar. “I’m cautiously optimistic as we’re going forward.”

A New Calm

For most of the past few years, the Government Center in downtown Ramadi, the seat of the provincial government, was under near-continual siege by insurgents, who reduced it to little more than a bullet-ridden bunker of broken concrete, sandbags and trapped marines. Entering meant sprinting from an armored vehicle to the front door of the building to evade snipers’ bullets.

Now, however, the compound and nearby buildings are being renovated to create offices for the provincial administration, council and governor. Hotels are being built next door for the waves of visitors the government expects once it is back in business.

On the roof of the main building, Capt. Jason Arthaud, commander of Company B, First Battalion, Sixth Marines, said the building had taken no sniper fire since November. “Just hours of peace and quiet,” he deadpanned. “And boredom.”

Violence has fallen swiftly throughout Ramadi and its sprawling rural environs, residents and American and Iraqi officials said. Last summer, the American military recorded as many as 25 violent acts a day in the Ramadi region, ranging from shootings and kidnappings to roadside bombs and suicide attacks. In the past several weeks, the average has dropped to four acts of violence a day, American military officials said.

On a recent morning, American and Iraqi troops, accompanied by several police officers, went on a foot patrol through a market in the Malaab neighborhood of Ramadi. Only a couple of months ago, American and Iraqi forces would enter the area only in armored vehicles. People stopped and stared. The sight of police and military forces in the area, particularly on foot, was still novel.

The new calm is eerie and unsettling, particularly for anyone who knew the city even several months ago.

“The complete change from night to day gives me pause,” said Capt. Brice Cooper, 26, executive officer of Company B, First Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, First Infantry Division, which has been stationed in the city and its outskirts since last summer. “A month and a half ago we were getting shot up. Now we’re doing civil affairs work.”

A Moderate Front

The turnabout began last September, when a federation of tribes in the Ramadi area came together as the Anbar Salvation Council to oppose the fundamentalist militants of Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia.

Among the council’s founders were members of the Abu Ali Jassem tribe, based in a rural area of northern Ramadi. The tribe’s leader, Sheik Tahir Sabbar Badawie, said in a recent interview that members of his tribe had fought in the insurgency that kept the Americans pinned down on their bases in Anbar for most of the last four years.

“If your country was occupied by Iraq, would you fight?” he asked, smiling knowingly. “Enough said.”

But while the anti-American sheiks in Anbar and Al Qaeda both opposed the Americans, their goals were different. The sheiks were part of a relatively moderate front that sought to drive the Americans out of Iraq; some were also fighting to restore Sunni Arab power. But Al Qaeda wanted to go even further and impose a fundamentalist Islamic state in Anbar, a plan that many of the sheiks did not share.

Al Qaeda’s fighters began to use killing, intimidation and financial coercion to divide the tribes and win support for their agenda. They killed about 210 people in the Abu Ali Jassem tribe alone and kidnapped others, demanding ransoms as high as $65,000 per person, Sheik Badawie said.

For all the sheiks’ hostility toward the Americans, they realized that they had a bigger enemy, or at least one that needed to be fought first, as a matter of survival.

The council sought financial and military support from the Iraqi and American governments. In return the sheiks volunteered hundreds of tribesmen for duty as police officers and agreed to allow the construction of joint American-Iraqi police and military outposts throughout their tribal territories.

A similar dynamic is playing out elsewhere in Anbar, a desert region the size of New York State that stretches west of Baghdad to the Syrian and Jordanian borders. Tribal cooperation with the American and Iraqi commands has led to expanded police forces in the cities of Husayba, Hit, Rutba, Baghdadi and Falluja, officials say.

With the help of the Anbar sheiks, the military equation immediately became simpler for the Americans in Ramadi. The number of enemies they faced suddenly diminished, American and Iraqi officials said. They were able to move more freely through large areas. With the addition of the tribal recruits, the Americans had enough troops to build and operate garrisons in areas they cleared, many of which had never seen any government security presence before.

And the Americans were now fighting alongside people with a deep knowledge of the local population and terrain, and with a sense of duty, vengeance and righteousness.

“We know this area, we know the best way to talk to the people and get information from them,” said Capt. Hussein Abd Nusaif, a police commander in a neighborhood in western Ramadi, who carries a Kalashnikov with an Al Capone-style “snail drum” magazine. “We are not afraid of Al Qaeda. We will fight them anywhere and anytime.”

Beginning last summer and continuing through March, the American-led joint forces pressed into the city, block by block, and swept the farmlands on the city’s outskirts. In many places the troops met fierce resistance. Scores of American and Iraqi security troops were killed or wounded.

The Ramadi region is essentially a police state now, with some 6,000 American troops, 4,000 Iraqi soldiers, 4,500 Iraqi police officers and an auxiliary police force of 2,000, all local tribesmen, known as the Provincial Security Force. The security forces are garrisoned in more than 65 police stations, military bases and joint American-Iraqi combat outposts, up from no more than 10 a year ago. The population of the city is officially about 400,000, though the current number appears to be much lower.

To help control the flow of traffic and forestall attacks, the American military has installed an elaborate system of barricades and checkpoints. In some of the enclaves created by this system, which American commanders frequently call “gated communities,” no vehicles except bicycles and pushcarts are allowed for fear of car bombs.

American commanders see the progress in Anbar as a bellwether for the rest of country. “One of the things I worry about in Baghdad is we won’t have the time to do the same kind of thing,” Lt. Gen. Raymond T. Odierno, commander of day-to-day war operations in Iraq, said in an interview here.

Yet the fact that Anbar is almost entirely Sunni and not riven by the same sectarian feuds as other violent places, like Baghdad and Diyala Province, has helped to establish order. Elsewhere, security forces are largely Shiite and are perceived by many Sunnis as part of the problem. In Anbar, however, the new police force reflects the homogeneous face of the province and, most critically, appears to enjoy the support of the vast majority of the people.

A Growing Police Force

Military commanders say they cannot completely account for the whereabouts of the insurgency. They say they believe that many guerrillas have been killed, while others have gone underground, laid down their arms or migrated to other parts of Anbar, particularly the corridor between Ramadi and Falluja, the town of Karma north of Falluja and the sprawling rural zones around Falluja, including Zaidon and Amariyat al-Falluja on the banks of the Euphrates River. American forces come under attack in these areas every day.

Still other guerrillas, the commanders acknowledge, have joined the police force, sneaking through a vetting procedure that is set up to catch only known suspects. Many insurgents “are fighting for a different side now,” said Brig. Gen. Mark Gurganus, commander of ground forces in Anbar. “I think that’s where the majority have gone.”

But American commanders say they are not particularly worried about infiltrators among the new recruits. Many of the former insurgents now in the police, they say, were probably low-level operatives who were mainly in it for the money and did relatively menial tasks, like planting roadside bombs.

The speed of the buildup has led to other problems. Hiring has outpaced the building of police academies, meaning that many new officers have been deployed with little or no training. Without enough uniforms, many new officers patrol in civilian clothes, some with their heads wrapped in scarves or covered in balaclavas to conceal their identities. They look no different than the insurgents shown in mujahedeen videos.

Commanders seem to regard these issues as a necessary cost of quickly building a police force in a political environment that is, in the words of Colonel Koenig, “sort of like looking through smoke.” The police force, they say, has been the most critical component of the new security plan in Anbar Province and the key to sustaining the military successes.

Yet, oversight of the police forces by American forces and the central Iraqi government is weak, leaving open the possibility that some local leaders are using newly armed tribal members as their personal death squads to settle old scores.

Several American officers who work with the Iraqi police said a lot of police work was conducted out of their view, particularly at night. “It’s like the Mafia,” one American soldier at an outpost in Juwayba said.

General Odierno said, “We have to watch them very closely to make sure we’re not forming militias.”

But there is a new sense of commitment by the police, American and Iraqi officials say, in part because they are patrolling their own neighborhoods. Many were motivated to join after they or their communities were attacked by Al Qaeda, and their successes have made them an even greater target of insurgent car bombs and suicide attacks.

Abd Muhammad Khalaf, 28, a policeman in the Jazeera district on Ramadi’s northern edge, is typical. He joined the police after Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia killed two of his brothers, he said. “I will die when God wills it,” he said. “But before I die, I will support my friends and kill some terrorists.”

The Tasks Ahead

Some tribal leaders now working with the Americans say they harbor deep resentment toward the Shiite-led administration of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, accusing it of pursuing a sectarian agenda. Yet they also say they are invested in the democratic process now.

After boycotting the national elections in 2005, many are now planning to participate in the next round of provincial elections, which have yet to be scheduled, as a way to build on the political and military gains they have made in recent months.

“Since I was a little boy, I have seen nothing but warfare — against the Kurds, Iranians, Kuwait, the Americans,” Sheik Badawie, the tribal leader, said. “We are tired of war. We are going to fight through the ballot box.”

Already, tribal leaders are participating in local councils that have been formed recently throughout the Ramadi area under the guidance of the American military.

Iraqi and American officials say the sheiks’ embrace of representative government reflects the new realities of power in Anbar. “Out here it’s been, ‘Who can defend his people?’ ” said Brig. Gen. John R. Allen, deputy commanding general of coalition forces in Anbar. “After the war it’s, ‘Who was able to reconstruct?’ ”

Indeed, American and Iraqi officials say that to hold on to the security gains and the public’s support, they must provide services to residents in areas they have tamed.

But successful development, they argue, will depend on closing the divide between the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad, which has long ignored the province, and the local leadership in Anbar, which has long tried to remain independent from the capital. If that fails, they say, the Iraqi and American governments may have helped to organize and arm a potent enemy.

Uneasy Alliance Is Taming One Insurgent Bastion

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

The purpose and effect of Observation Post Hawk

Cpl. Paul Robbins Jr.

I Marine Expeditionary Force

Marine Corps News

2007-04-23

AR RAMADI, Iraq (April 23, 2007) -- Observation Post Hawk is one of 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment’s original posts, standing on the eastern most edge of the battalion’s area of responsibility in West Central Ramadi, Iraq.

The main focus of the Charlie Company manned OP was to provide security for and around the city’s main medical facility, the Ramadi General Hospital.

Working against a determined enemy, the Marines worked side-by-side with Iraqi Security Forces to return the city’s largest civilian care facility to its people.

ROUGH BEGINNINGS, FIGHTING FOR CONTROL

In the early stages of 1/6’s deployment, the Marines at OP Hawk were kept busy by an area containing an active insurgent presence.

The observation post would sometimes see several small-arms or mortar attacks per day, while Marines and Iraqi soldiers conducted operations to help stem the violence.

“We did a lot of patrols when we first got here to put boots out on the ground,” said Sgt. Jason E. Wing, 22-year-old sergeant of the guard at OP Hawk. “The area was still heavily contested.”

Insurgent attacks and activity in the area centered around the Ramadi General Hospital, a valuable component in the city’s infrastructure.

The Ramadi General Hospital is the area’s premiere medical facility, with a medical staff of more than 260 doctors and emergency care personnel.

The facility remained available to local citizens and the staff was cooperative with Coalition Forces, but insurgents maintained some level of freedom in the hospital as well.

Using intimidation tactics on the staff and residents, insurgents were able to utilize the facility when Marines and Iraqi forces were not in the area.

“The insurgents used to have some freedom in the hospital,” said 1st Lt. Aaron M. Zimmerman, 25-year-old platoon commander at OP Hawk. “They used to be able to bring their wounded into the hospital for care.”

To loosen the grip of the insurgency in the area, the Marines of OP Hawk, assisted by soldiers of the Iraqi Army’s 4th Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade, 7th Division, kept constant pressure on the insurgents with observation from fixed positions and regular patrols.

Over the following months, the combined strength of the Marines and Iraqi Army made insurgent movement difficult, opening a pathway for civil military operations in the hospital and local neighborhoods.

“Through our operations, we were able to push the insurgents back and open lines of communication with the people,” said Zimmerman, a native of Naples, Fla.

Recognizing the importance of the residents’ cooperation, the Marines of OP Hawk, assisted by a civil affairs team and their Iraqi Army counterparts, began a push to win over the locals with community aid projects.

While continuing to provide a significant security presence in the area, most notably building Iraqi Army guard posts at the hospital, the combined force provided fuel, food, generators, and much needed medical supplies to the hospital and surrounding community.

The continuous aid and support of the local families, combined with a decrease in insurgent activity, caused the majority of people in the area to increase their cooperation with Marine and Iraqi Security Forces.

“The insurgency cannot provide the things we can, so the people quickly realized that they are better off working with us,” said Zimmerman.

SUCCESS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

Now several months later in the deployment, a large measure of success can be seen in the area surrounding OP Hawk.

For the Marines now manning the post, success is easily measured by the number of attacks received recently.

“We’ve gone from having several attacks a day in the early stages to, now, not having a single attack in weeks,” said Wing, a native of Lewiston, Maine.

For the residents of the area and Iraqi soldiers securing the hospital, success is shown in their abilities to prevent the insurgents’ return.

“Insurgents can no longer come here discreetly for treatment because my soldiers are here to detain them,” said Maj. Jabbar, 42-year-old commanding officer of 4th Company. “Around here, insurgents cannot even move through the streets because the Iraqi Army and Marines are watching.”

Although the efforts of the Marines and Iraqi soldiers at OP Hawk were vital in beginning the process, much of the decline in insurgent activity can be attributed to the battalion’s strategy of installing joint security stations throughout West Central Ramadi.

Through this process, Marines, Iraqi soldiers and Iraqi police establish and operate numerous forward bases in key areas of the city.

These security stations provide an increased security presence and introduce Iraqi Security Forces to the people of the area, which has had a significant impact on insurgent activity.

“After (Joint Security Station) Qatana and OP North went up, it really made a big difference here,” said Zimmerman. “With the decrease in activity, we were able to work with the hospital staff daily.”

While the Marines and Iraqi soldiers at OP Hawk had always assisted the hospital when they could, the opportunity to work with the hospital every day made a significant difference.

“Talking to them every day, we’re able to get them what they actually need, not what we ‘think’ they need,” said Zimmerman.

With solid security in place and continued support from both Marines and Iraqi Security Forces, the local populace has repeatedly expressed their appreciation to the combined force.

“The people are happy because we keep the area under control,” said Jabbar. “They appreciate our efforts and what we’ve done here.”

A DIFFERENT ROLE

The nearly complete success in OP Hawk’s area of responsibility has led to a change in roles for the Marines operating there.

In the beginning, Marines led operations to give complete control of the hospital back to the residents and win over the local populace, but now, the Marines are just a helping hand.

“Our purpose here is to assist the Iraqi Army in maintaining control of the hospital and local neighborhoods,” said Wing. “We’ve gone from a proactive role in security to letting the Iraqi Security Forces take over.”

The Marines’ role in security has been pulled back to standing post at fixed positions and conducting civil military operations to aid the people, allowing Iraqi Security Forces to take the lead on security in the neighborhoods.

In recent months, the majority of boots on the streets are those of the Iraqi Army.

“It seems like the only ‘patrolling’ we do now is our visits to the hospital,” said Wing.

With their decreased security role, the Marines of OP Hawk will remain focused on assisting the staff of the Ramadi General Hospital and working alongside civil affairs Marines to improve the surrounding area.

Although many of the Marines attribute the area’s continued success to their Iraqi counterparts’ hard work, the soldiers of 4th Company say it couldn’t be done without them.

“The cooperation between the Marines and Iraqi soldiers has made Ramadi safer,” said Jabbar. “We could not accomplish as much as we have without the Marines.”

Major Jabbar, 42-year-old commanding officer of the 4th Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade, 7th Division, speaks with staff from the Ar Ramadi General Hospital during a patrol in West Central Ar Ramadi April 7, 2007.

Sergeant Jason E. Wing, 22-year-old sergeant of the guard for Company C, 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, plays a game of team ping pong with a soldier of the Iraqi Army as a teammate. Marines have worked alongside Iraqi soldiers to at Observation Post Hawk in Ar Ramadi, Iraq, to make the area safer for local residents.

The purpose and effect of Observation Post Hawk

I Marine Expeditionary Force

Marine Corps News

2007-04-23

AR RAMADI, Iraq (April 23, 2007) -- Observation Post Hawk is one of 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment’s original posts, standing on the eastern most edge of the battalion’s area of responsibility in West Central Ramadi, Iraq.

The main focus of the Charlie Company manned OP was to provide security for and around the city’s main medical facility, the Ramadi General Hospital.

Working against a determined enemy, the Marines worked side-by-side with Iraqi Security Forces to return the city’s largest civilian care facility to its people.

ROUGH BEGINNINGS, FIGHTING FOR CONTROL

In the early stages of 1/6’s deployment, the Marines at OP Hawk were kept busy by an area containing an active insurgent presence.

The observation post would sometimes see several small-arms or mortar attacks per day, while Marines and Iraqi soldiers conducted operations to help stem the violence.

“We did a lot of patrols when we first got here to put boots out on the ground,” said Sgt. Jason E. Wing, 22-year-old sergeant of the guard at OP Hawk. “The area was still heavily contested.”

Insurgent attacks and activity in the area centered around the Ramadi General Hospital, a valuable component in the city’s infrastructure.

The Ramadi General Hospital is the area’s premiere medical facility, with a medical staff of more than 260 doctors and emergency care personnel.

The facility remained available to local citizens and the staff was cooperative with Coalition Forces, but insurgents maintained some level of freedom in the hospital as well.

Using intimidation tactics on the staff and residents, insurgents were able to utilize the facility when Marines and Iraqi forces were not in the area.

“The insurgents used to have some freedom in the hospital,” said 1st Lt. Aaron M. Zimmerman, 25-year-old platoon commander at OP Hawk. “They used to be able to bring their wounded into the hospital for care.”

To loosen the grip of the insurgency in the area, the Marines of OP Hawk, assisted by soldiers of the Iraqi Army’s 4th Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade, 7th Division, kept constant pressure on the insurgents with observation from fixed positions and regular patrols.

Over the following months, the combined strength of the Marines and Iraqi Army made insurgent movement difficult, opening a pathway for civil military operations in the hospital and local neighborhoods.

“Through our operations, we were able to push the insurgents back and open lines of communication with the people,” said Zimmerman, a native of Naples, Fla.

Recognizing the importance of the residents’ cooperation, the Marines of OP Hawk, assisted by a civil affairs team and their Iraqi Army counterparts, began a push to win over the locals with community aid projects.

While continuing to provide a significant security presence in the area, most notably building Iraqi Army guard posts at the hospital, the combined force provided fuel, food, generators, and much needed medical supplies to the hospital and surrounding community.

The continuous aid and support of the local families, combined with a decrease in insurgent activity, caused the majority of people in the area to increase their cooperation with Marine and Iraqi Security Forces.

“The insurgency cannot provide the things we can, so the people quickly realized that they are better off working with us,” said Zimmerman.

SUCCESS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

Now several months later in the deployment, a large measure of success can be seen in the area surrounding OP Hawk.

For the Marines now manning the post, success is easily measured by the number of attacks received recently.

“We’ve gone from having several attacks a day in the early stages to, now, not having a single attack in weeks,” said Wing, a native of Lewiston, Maine.

For the residents of the area and Iraqi soldiers securing the hospital, success is shown in their abilities to prevent the insurgents’ return.

“Insurgents can no longer come here discreetly for treatment because my soldiers are here to detain them,” said Maj. Jabbar, 42-year-old commanding officer of 4th Company. “Around here, insurgents cannot even move through the streets because the Iraqi Army and Marines are watching.”

Although the efforts of the Marines and Iraqi soldiers at OP Hawk were vital in beginning the process, much of the decline in insurgent activity can be attributed to the battalion’s strategy of installing joint security stations throughout West Central Ramadi.

Through this process, Marines, Iraqi soldiers and Iraqi police establish and operate numerous forward bases in key areas of the city.

These security stations provide an increased security presence and introduce Iraqi Security Forces to the people of the area, which has had a significant impact on insurgent activity.

“After (Joint Security Station) Qatana and OP North went up, it really made a big difference here,” said Zimmerman. “With the decrease in activity, we were able to work with the hospital staff daily.”

While the Marines and Iraqi soldiers at OP Hawk had always assisted the hospital when they could, the opportunity to work with the hospital every day made a significant difference.

“Talking to them every day, we’re able to get them what they actually need, not what we ‘think’ they need,” said Zimmerman.

With solid security in place and continued support from both Marines and Iraqi Security Forces, the local populace has repeatedly expressed their appreciation to the combined force.

“The people are happy because we keep the area under control,” said Jabbar. “They appreciate our efforts and what we’ve done here.”

A DIFFERENT ROLE

The nearly complete success in OP Hawk’s area of responsibility has led to a change in roles for the Marines operating there.

In the beginning, Marines led operations to give complete control of the hospital back to the residents and win over the local populace, but now, the Marines are just a helping hand.

“Our purpose here is to assist the Iraqi Army in maintaining control of the hospital and local neighborhoods,” said Wing. “We’ve gone from a proactive role in security to letting the Iraqi Security Forces take over.”

The Marines’ role in security has been pulled back to standing post at fixed positions and conducting civil military operations to aid the people, allowing Iraqi Security Forces to take the lead on security in the neighborhoods.

In recent months, the majority of boots on the streets are those of the Iraqi Army.

“It seems like the only ‘patrolling’ we do now is our visits to the hospital,” said Wing.

With their decreased security role, the Marines of OP Hawk will remain focused on assisting the staff of the Ramadi General Hospital and working alongside civil affairs Marines to improve the surrounding area.

Although many of the Marines attribute the area’s continued success to their Iraqi counterparts’ hard work, the soldiers of 4th Company say it couldn’t be done without them.

“The cooperation between the Marines and Iraqi soldiers has made Ramadi safer,” said Jabbar. “We could not accomplish as much as we have without the Marines.”

Major Jabbar, 42-year-old commanding officer of the 4th Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade, 7th Division, speaks with staff from the Ar Ramadi General Hospital during a patrol in West Central Ar Ramadi April 7, 2007.

Sergeant Jason E. Wing, 22-year-old sergeant of the guard for Company C, 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, plays a game of team ping pong with a soldier of the Iraqi Army as a teammate. Marines have worked alongside Iraqi soldiers to at Observation Post Hawk in Ar Ramadi, Iraq, to make the area safer for local residents.

The purpose and effect of Observation Post Hawk

HERO REIDS DEM THE RIOT ACT

By GEOFF EARLE, Post Correspondent

April 24, 2007 -- WASHINGTON - A tough U.S. Marine stationed in one of the most hostile areas of Iraq has a message for Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid: "We need to stay here and help rebuild."

In raw and emotional language from the bloody front lines, Cpl. Tyler Rock, of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, skewered Reid for being far removed from the patriotism and progress in Iraq.

"Yeah, and I got a quote for that [expletive] Harry Reid. These families need us here," Rock vented in an e-mail to Pat Dollard, a Hollywood agent-turned-war reporter who posted the comment on his Web site, www.patdollard.com.

"Obviously [Reid] has never been in Iraq. Or at least the area worth seeing . . .the parts where insurgency is rampant and the buildings are blown to pieces," Rock wrote.

Based in Camp Lejeune, N.C., Rock catalogued a series of grim daily traumas in Iraq, like getting covered in ash and sleeping under a dirty rug in an Iraqi family's house, or watching "several terrorists die" on the same strip of pavement.

But he says he is optimistic about the future of a country that he says has "turned to complete s- - -" during a bloody insurgency.

He also spoke admiringly of the risks brave Iraqi citizens take every day.

"If Iraq didn't want us here then why do we have [Iraqi police] volunteering every day to rebuild their cities?" he asked.

"It sucks that Iraqis have more patriotism for a country that has turned to complete s- - - more than the people in America who drink Starbucks every day.

"We could leave this place and say we are sorry to the terrorists. And then we could wait for 3,000 more American civilians to die before we say, 'Hey, that's not nice' again."

"And the sad thing is after we WIN this war. People like [Reid] will say he was there for us the whole time."

Rock's candid e-mail swept across the Internet after Dollard posted it on his site, and it was picked up by the Drudge Report and numerous other Web sites.

"What does [Reid] know about us 'losing' besides what he wants to believe? The truth is that we are pushing al Qaeda out and we are pushing the insurgency out. We are here to support a nation."

HERO REIDS DEM THE RIOT ACT

April 24, 2007 -- WASHINGTON - A tough U.S. Marine stationed in one of the most hostile areas of Iraq has a message for Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid: "We need to stay here and help rebuild."

In raw and emotional language from the bloody front lines, Cpl. Tyler Rock, of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, skewered Reid for being far removed from the patriotism and progress in Iraq.

"Yeah, and I got a quote for that [expletive] Harry Reid. These families need us here," Rock vented in an e-mail to Pat Dollard, a Hollywood agent-turned-war reporter who posted the comment on his Web site, www.patdollard.com.

"Obviously [Reid] has never been in Iraq. Or at least the area worth seeing . . .the parts where insurgency is rampant and the buildings are blown to pieces," Rock wrote.

Based in Camp Lejeune, N.C., Rock catalogued a series of grim daily traumas in Iraq, like getting covered in ash and sleeping under a dirty rug in an Iraqi family's house, or watching "several terrorists die" on the same strip of pavement.

But he says he is optimistic about the future of a country that he says has "turned to complete s- - -" during a bloody insurgency.

He also spoke admiringly of the risks brave Iraqi citizens take every day.

"If Iraq didn't want us here then why do we have [Iraqi police] volunteering every day to rebuild their cities?" he asked.

"It sucks that Iraqis have more patriotism for a country that has turned to complete s- - - more than the people in America who drink Starbucks every day.

"We could leave this place and say we are sorry to the terrorists. And then we could wait for 3,000 more American civilians to die before we say, 'Hey, that's not nice' again."

"And the sad thing is after we WIN this war. People like [Reid] will say he was there for us the whole time."

Rock's candid e-mail swept across the Internet after Dollard posted it on his site, and it was picked up by the Drudge Report and numerous other Web sites.

"What does [Reid] know about us 'losing' besides what he wants to believe? The truth is that we are pushing al Qaeda out and we are pushing the insurgency out. We are here to support a nation."

HERO REIDS DEM THE RIOT ACT

Lejeune Marines to return from Iraq Tuesday

Staff report

Posted : Monday Apr 23, 2007 15:43:29 EDT

JACKSONVILLE, N.C. — More than 250 leathernecks are scheduled to return to Camp Lejeune, N.C., from Iraq on Tuesday.

Nearly 150 of the Marines are with 2nd Tank Battalion, according to a II Marine Expeditionary Force spokesman.

Marines with other Lejeune units, including 2nd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion; 1st Battalion, 6th Marines; and 2nd Assault Amphibian Battalion, are coming home as well.

The leathernecks are returning from a seven-month deployment to Iraq’s Anbar province.

Lejeune Marines to return from Iraq Tuesday

Posted : Monday Apr 23, 2007 15:43:29 EDT

JACKSONVILLE, N.C. — More than 250 leathernecks are scheduled to return to Camp Lejeune, N.C., from Iraq on Tuesday.

Nearly 150 of the Marines are with 2nd Tank Battalion, according to a II Marine Expeditionary Force spokesman.

Marines with other Lejeune units, including 2nd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion; 1st Battalion, 6th Marines; and 2nd Assault Amphibian Battalion, are coming home as well.

The leathernecks are returning from a seven-month deployment to Iraq’s Anbar province.

Lejeune Marines to return from Iraq Tuesday

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

Update from Battalion Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel William M. Jurney

Dear Families and Friends of 1/6,

I want to thank each of you for your continued support and commitment to our mission here. Despite the extension your loved ones remain strong and professional. They are 1/6 HARD.

Your Marines and Sailors have accomplished so much during our time here in Iraq. We have exceeded expectations. We consistently hear from those who come here whether it be reporters or official representatives… all comment on what a difference they see from the time they spent with us back in August/September to now. They are simply amazed and question why the progress we are making isn’t making headline news. They are overwhelmed at what we have done and continue to do in helping secure and stabilize this part of Ramadi.

I am sure everyone is starting to focus in on the details of when we are coming home. I will provide you with the projected timelines below:

Our projected window for return looks to be around 17-22 May. We will arrive on different flights/planes on different days. Remember we are moving over 1000 Marines and Sailors half way across the world.

We will enjoy some time off in the local area during Memorial Day Weekend from Friday May 25th until Tuesday, May 29th ; however, Marines and Sailors will not be allowed to leave the Jacksonville area until 1 June. The post deployment leave period where everyone will request leave will begin at 1200 on 1 June and end at 5pm on 26 June - This leave period still requires that each individual receive specific approval for his request.

The Advanced Party which will be a very small group, is anticipated to arrive sometime during the first week of May. Our 1/6 Military Transition Team (MTT) remains on schedule and should return around the April 23-24 time frame.

Additionally, May 25th is the scheduled date for the battalion Memorial service where we will honor our fallen brothers.

As we get closer to these dates, please know that you will be informed. We will update the 1-800 number as often as we can and as always, you are welcome to call our FRSNCO, SSgt Martins at (910) 451-2407 or (910) 546-9133. Once your Marine or Sailor is informed of the specific plan/flight that he will be assigned, he will be able to contact you with that information or you can contact our FRSNCO who will also have that information. For security reasons, I know you understand why we will not post those types of details on the website.

Please be patient. Your Marines and Sailors will not have those specifics until approximately one week prior to our return. Anything you hear otherwise is a “rumor” and should be treated as such… I know it is frustrating -- but let’s remember that our priority remains to keep these guys focused on the mission at hand and I need your help now more than ever to accomplish this.

Again, I thank you for your continued support of 1/6. God bless you all for the strength and sacrifice you have shown in supporting these brave men.

In your service,

W. M. Jurney

Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps

Commanding Officer, 1st Battalion 6th Marines

I want to thank each of you for your continued support and commitment to our mission here. Despite the extension your loved ones remain strong and professional. They are 1/6 HARD.

Your Marines and Sailors have accomplished so much during our time here in Iraq. We have exceeded expectations. We consistently hear from those who come here whether it be reporters or official representatives… all comment on what a difference they see from the time they spent with us back in August/September to now. They are simply amazed and question why the progress we are making isn’t making headline news. They are overwhelmed at what we have done and continue to do in helping secure and stabilize this part of Ramadi.

I am sure everyone is starting to focus in on the details of when we are coming home. I will provide you with the projected timelines below:

Our projected window for return looks to be around 17-22 May. We will arrive on different flights/planes on different days. Remember we are moving over 1000 Marines and Sailors half way across the world.

We will enjoy some time off in the local area during Memorial Day Weekend from Friday May 25th until Tuesday, May 29th ; however, Marines and Sailors will not be allowed to leave the Jacksonville area until 1 June. The post deployment leave period where everyone will request leave will begin at 1200 on 1 June and end at 5pm on 26 June - This leave period still requires that each individual receive specific approval for his request.

The Advanced Party which will be a very small group, is anticipated to arrive sometime during the first week of May. Our 1/6 Military Transition Team (MTT) remains on schedule and should return around the April 23-24 time frame.

Additionally, May 25th is the scheduled date for the battalion Memorial service where we will honor our fallen brothers.

As we get closer to these dates, please know that you will be informed. We will update the 1-800 number as often as we can and as always, you are welcome to call our FRSNCO, SSgt Martins at (910) 451-2407 or (910) 546-9133. Once your Marine or Sailor is informed of the specific plan/flight that he will be assigned, he will be able to contact you with that information or you can contact our FRSNCO who will also have that information. For security reasons, I know you understand why we will not post those types of details on the website.

Please be patient. Your Marines and Sailors will not have those specifics until approximately one week prior to our return. Anything you hear otherwise is a “rumor” and should be treated as such… I know it is frustrating -- but let’s remember that our priority remains to keep these guys focused on the mission at hand and I need your help now more than ever to accomplish this.

Again, I thank you for your continued support of 1/6. God bless you all for the strength and sacrifice you have shown in supporting these brave men.

In your service,

W. M. Jurney

Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps

Commanding Officer, 1st Battalion 6th Marines

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

Quote

We sleep safe in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would do us harm. --George Orwell

Sunday, April 15, 2007

Mount Vernon Marine returns home from Iraq to stay

By LEN MANIACE

THE JOURNAL NEWS

(Original publication: April 15, 2007)

MOUNT VERNON - For much of the evening, Marine Sgt. Daniel Fondanella was too busy to stop by the buffet table that was stuffed with chicken, pasta salad and a huge Italian hero.

He was busy greeting friends and family who held a party to welcome the 27-year-old Marine back from Iraq, this time to stay.

Jason McKenna - Fondanella's best friend since the two were 6 growing up in New Rochelle -was among them. An hour earlier, McKenna was at La Guardia Airport about to board a plane back to law school in North Carolina, cutting short his visit with Fondanella due to the predicted nor'easter. But then he changed his mind again.

"I couldn't miss this. I'll get back somehow," said McKenna, as he stood in the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 596 Hall on South Third Avenue.

After four years in the Marines, Fondanella was discharged on April 6. Serving with the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, Fondanella was on three combat tours, each about seven months, one in Afghanistan and two in Iraq.

There were ambushes to contend with in Afghanistan and roadside bombs during his first Iraqi tour in Fallujah. The last tour, in Ramadi, was worse, he said.

"In Ramadi, they did both," Fondanella said.

His grandmother, Bonney Creighton, reminded him about the rosary beads she had given him before he left for basic training in Parris Island, S.C.

The prayer beads had belonged to her father, who served with the Canadian Army in World War I.

"I carried them in my breast pocket wherever I went," Fondanella said.

Fondanella's girlfriend, Venessa Muoio, said she can now stop worrying.

The couple stayed in touch mostly through the Internet. They could talk only weekly when Fondanella was in Fallujah, but more frequently in the more hazardous Ramadi, where missions lasted only three days.

Because of the time difference, Fondanella was usually available to talk at 3 a.m., so the two worked out an elaborate system. He would text message her cell phone, waking her. Muoio would boot up her computer and the two would chat on the Internet. Because her computer was equipped with a webcam, Fondanella could see Muoio from half a world away.

"I would hurry and brush my hair and put on lipstick first," Muoio said, laughing.

Asked about his most difficult moments during the four years, Fondanella said it was the death of four members of his company. Fondanella was promoted to sergeant last fall, and he was responsible for telling his troops.

"It was especially tough when it involved someone you had been talking to a few minutes before," Fondanella said.

The best moment probably was a New Year's Eve celebration that greeted 2007 when Marines were able to exchange helmets and weapons for party hats and noise makers.

"Just seeing everybody making the best of it was great," Fondanella said.

Though Ramadi was the most dangerous tour, Fondanella said there were clear signs that life was improving for the people living there during his stay.

"We were making them feel more safe as time went on. Where women wouldn't ever walk around, you would see them. Schools opened and a hospital, too," Fondanella said. "And it had become a safer place for us, too."

Described by his mother, Gale, as the family comedian, Fondanella worked at several jobs, including a supervisory stint at a video store and a New Rochelle country club, before he decided to enlist in the Marine Corps in April 2003.

"I remember watching the Gulf War on TV, and when we were going to go to war in Iraq, I wanted to be that guy doing the same thing," Fondanella recalled.

Now, Fondanella is making plans for life after the Marines. He wants to take a firefighters test for several Westchester fire departments. It's a job he has thought about since he was a child.

He returned to New York in mid-March, just in time for a trip to the St. Patrick's Day parade in Manhattan and a belated Thanksgiving dinner in the family's home in Mount Vernon.

"We had turkey, stuffing the whole thing," Gale Fondanella said. "We had a lot to be thankful for."

Dan Fondanella often thinks about the men he served with who are still in Iraq. "It feels good to be back, but it will feel better when I know all my guys are back, too," Fondanella said.

McKenna said he supported his friend's decision to join the Marines, though he worried about his safety. But McKenna added that he was confident that his old friend would safely return.

"He is a survivor," McKenna said. "We didn't come up in the most affluent homes. But he did good. He's got something in him."

Mount Vernon Marine returns home from Iraq to stay

THE JOURNAL NEWS

(Original publication: April 15, 2007)

MOUNT VERNON - For much of the evening, Marine Sgt. Daniel Fondanella was too busy to stop by the buffet table that was stuffed with chicken, pasta salad and a huge Italian hero.

He was busy greeting friends and family who held a party to welcome the 27-year-old Marine back from Iraq, this time to stay.

Jason McKenna - Fondanella's best friend since the two were 6 growing up in New Rochelle -was among them. An hour earlier, McKenna was at La Guardia Airport about to board a plane back to law school in North Carolina, cutting short his visit with Fondanella due to the predicted nor'easter. But then he changed his mind again.

"I couldn't miss this. I'll get back somehow," said McKenna, as he stood in the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 596 Hall on South Third Avenue.

After four years in the Marines, Fondanella was discharged on April 6. Serving with the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, Fondanella was on three combat tours, each about seven months, one in Afghanistan and two in Iraq.

There were ambushes to contend with in Afghanistan and roadside bombs during his first Iraqi tour in Fallujah. The last tour, in Ramadi, was worse, he said.

"In Ramadi, they did both," Fondanella said.

His grandmother, Bonney Creighton, reminded him about the rosary beads she had given him before he left for basic training in Parris Island, S.C.

The prayer beads had belonged to her father, who served with the Canadian Army in World War I.

"I carried them in my breast pocket wherever I went," Fondanella said.

Fondanella's girlfriend, Venessa Muoio, said she can now stop worrying.

The couple stayed in touch mostly through the Internet. They could talk only weekly when Fondanella was in Fallujah, but more frequently in the more hazardous Ramadi, where missions lasted only three days.