By Alexa James

Times Herald-Record May 13, 2007

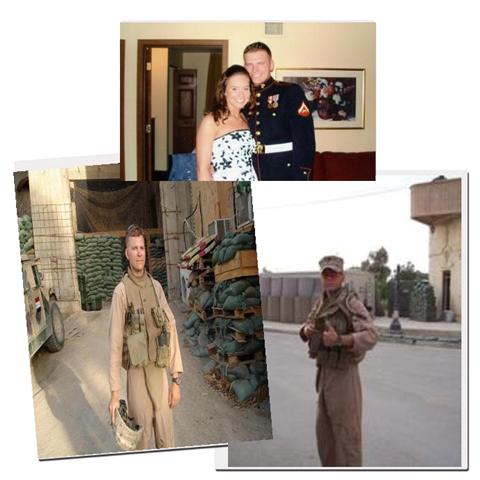

Times Herald-Record Reporter Alexa James has spent more than six months following the Siruchek family as they await the return of their son and brother, Matt, from service in Iraq. He is scheduled to return to the United States this month. The family has struggled with the heart-wrenching emotions of having a loved one in harm’s way. These are portraits of that story.

The father: September 2006

Speeding south down Interstate 95, Adam Siruchek glances sideways at his son sleeping in the passenger seat. He reaches over, pats his leg.

Not to wake him. Just to feel the knee. Squeeze it. Remember it.

Over 11 hours, across some 650 miles, Adam wills himself to memorize such details as father and son make their way from the Village of Walden to the military metropolis of Jacksonville, N.C.

Once there, at Camp Lejeune, base to the world's largest concentration of Marines and sailors, a dad will have a short time to cement 20 years worth of son into his memory.

Raising Matthew Siruchek was a turbulent ride. Bullheaded and needling, Adam's oldest boy was fiercely independent. Push Matt in the right direction, and he'd shove back, harder.

The U.S. Navy had squared his son's stubborn streak, much as it had for Adam, now 44, a quarter-century ago. The world was a different place then.

Adam wanted his son to stay "blue side," serving his time stateside or aboard a ship "and wearing dungarees and a white hat and floating in the middle of the ocean somewhere."

Matt, the hardhead, went "green side" instead. He became a Navy hospital corpsman, a medic, assigned to look after the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment in Iraq. In the name of Operation Iraqi Freedom, they were headed to Ramadi, capital of the Anbar province, a city on the southwest corner of the Sunni Triangle, about 30 miles west of Fallujah. Ramadi street graffiti had tagged it the "graveyard of the Americans."

"If you wanted to get into the middle of it," Adam sighs, "that's the way to do it."

The deployment leads Adam through a minefield of questions. "Is this something that can be won? You know, this war on terror? Terror has been around for years and years," he says. "Are we making a difference?"

At least his son would be saving lives, he bargains with himself, not just taking them.

But this car ride, the last one before Iraq, can't be wasted on unknowns. Quickly, before it's time to say goodbye, a father and son must square away their past.

By the time Adam leaves the base, Matt has already changed into Marine Corps fatigues.

Adam tries to burn it all into his memory, to have it ready if he needs to recall it later.

"We'd had our share of turbulent times," he says. "I needed to make sure we were right with that. That all was forgiven."

Adam swallows hard.

He continues when it's safe. "Sometimes, I'll be driving around and I'll still see him sleeping in the car." He'll reach over and pat the empty seat.

"It's a great memory. Keeps me going."

The brother: December 2006

Erik Siruchek has heard it a hundred times. "You look just like your brother."

Matt Siruchek graduated and took off for Navy boot camp two years ago. Erik is 17 now and wrapping up his junior year at Valley Central High. Still, he is better known to his teachers as "Matt," or, if he's lucky, "Matt's little brother."

And that's fine. Erik thinks he'll probably go military, too. Special forces, he says, because he's "good at that military sneaking around stuff."

Most of Erik's life, it seems, has been lived on his big brother's terms. Sports, classes, girls: "I got my dad, but we don't really talk much about girls," he says. "Matt was the one I went to."

Matt taught Erik how to drive stick on his black convertible. "He used to make me start it on the hill in the driveway."

When he deployed, Matt told Erik to start it now and then, keep it running. One day, he told him he could take it to the prom. Erik declined. "If something happened to it he'd kill me."

It's not as if Matt doesn't trust Erik. Last summer, he often took him rock climbing on the Shawangunk Ridge. If he tried something risky, he'd make Erik stand by to brace the ropes. Erik would sweat bullets.

Since the deployment, Matt's requests have intensified. First came the wedding proposal. Erik was the first to know Matt's plans with his high school sweetheart. "We kind of shook hands," Erik recalls, "then he told me to work on my best man's speech and to look after his girl."

He also made Erik promise to spare him no bad news from the home front. "He gave me this whole speech about how even if everyone else doesn't tell him stuff, he wants me to tell him."

In time, Erik would have to tell Matt about Mom not feeling well, about Dad's new job, his sister's car crash. Everything.

The toughest demand came just before New Year's, when Matt asked Erik to go to Arlington National Cemetery.

A medic from Matt's Fleet Marine Force had died. Navy Hospital Corpsman Christopher Anderson, 24, from Colorado, was killed in a mortar attack Dec. 4.

Matt took it hard. "That kid, he pretty much kept Matt sane," Erik said. "He was his best friend."

Thirty Navy medics have died in Iraq and Afghanistan since September 2001, accounting for nearly 30 percent of Navy casualties.

The only members of Anderson's unit who could attend his funeral were those the medic had saved during his tour. Marines who had been sent home to heal showed up to say thanks to their "doc."

In section 60 of the 600-acre cemetery, Erik saw a Marine, missing both legs and one hand, offer condolences to the family. He saw snow-white gloves fold tight an American flag, heard the rifles crack and the bugle sound.

"I was OK for a while," he said, until the medic's brother approached the coffin. Erik lost it. After the funeral, after the somber crowd had wandered off, the brother was still standing there.

"Oh crap," Erik thought, "What if that's me next month?"

The sisters: February 2007

The Siruchek siblings are gathered in mom's living room, spilling popcorn, surfing MySpace, getting on and off their cells and trying to get the VCR to work.

"We're gonna miss Justin!" groans sister Jessica North, 23. The Grammy Awards are on tonight, and pop-throb Justin Timberlake will perform some hit single called "SexyBack." Jess "loves" Justin.

But the Grammy's are on at the same time as the season premier of "War Stories." The Fox News documentary tracks Lt. Colonel-turned-correspondent Oliver North, embedded in Ramadi with the 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment — these are Matt's Marines.

The girls get e-mail from Matt and the occasional phone call, but tonight they surround the TV in the hope that maybe, with any luck, he'll flash across the screen. Maybe that "pain-in-the-ass" brother, who they miss terribly now that he's thousands of miles away in one of the scariest places on Earth, will land himself a spot on national TV.

Of course, the VCR won't work, so Mom improvises. She sets up a camcorder to record the TV screen. Jessica abandons Justin.

"Justin will be up on YouTube tonight anyway," says little sister Sharon Siruchek, 18, signing onto AOL Instant Messenger to see if Matt's signed on in Iraq.

Families of soldiers in Iraq have unprecedented access to their deployed loved ones. Skirting official military channels, they can e-mail, text-message and post pictures and videos on any number of online social venues, such as MySpace.

That's how the girls found out about "War Stories." Matt had operated on a cameraman's ingrown toenail and posted some pictures of the procedure online. Fox news posted the same shots on their site, and later e-mailed Matt's mom.

"Not only can your son cut away an evil toenail," wrote cameraman Mal James, "he has the voice of an angel." James said he filmed Matt playing guitar and singing "Silent Night" at a church Christmas service in the barracks. Maybe that would make tonight's episode.

Fifteen minutes in, the show cuts to the mess hall and row after row of olive T-shirts hunched over trays of chow. On the left, one of the crew cuts looks up at the camera and smirks. It's just a second or two before the camera cuts away, but it's enough.

"There he is!" the girls squeal in unison. "Oh my God! That's Matt! That's his head!

Immediately, the laptop and the cell phones are flashing and beeping with text messages from friends watching around town. The girls work themselves into a frenzy. When "War Stories" cuts to a commercial, they flip back to the Grammys.

Justin Timberlake is halfway through his set.

The following week, Sharon is playing on her computer when she gets a disturbing text message from Matt:

"Hey, I got shot. lol."

The mother: May 2007

When she sleeps at all, Becky Siruchek sleeps with her cell phone. "Just in case."

In case her son calls again at 2 a.m. to tell her he's been shot.

"Don't worry," he told her. "I've been cut worse shaving."

Matt had been outside on a satellite phone with his fiancee when he heard the crack.

A sniper in an abandoned factory some 90 yards away fired on the medic. The bullet ricocheted into his stomach. He saved the 7.62 mm slug to show her.

"Just a couple of stitches and a Band-Aid." he said. "They told me to call you to say that I'm all right."

Becky was not. She had nightmares, lost her nerve in line at the grocery store, couldn't focus at work. The kids would ask her if she was OK and she'd scream, "My child was hit with a bullet! No! I'm not OK!"

But the rest of the world went on. Sharon was in a car accident and spent a few days in the hospital. Erik had play practice every night and was struggling in chemistry. Becky was falling behind in her night school classes too.

And all the while, on the news, Republicans rambled on about extended deployments, Democrats countered for withdrawals, the Defense Department begged for billions of dollars and soldiers kept blowing up.

"I feel like I've aged a decade in the last six months," Becky says. "It's the anticipatory grief, living in expectation or fear of a loss. Now I feel extra tension because we're in the homestretch."

Matt is due home this month. He's already started shipping stuff back: a flight suit, a guitar amp, DVDs and books. "Here's my little piece of Iraq," says Becky, holding up a medicine bottle filled with sand.

"I just want him out of there."

And then what?

Matt won't be the same. He's spent seven months holding pressure to bleeding bodies, plucking shrapnel, stitching flesh back together. He treats the coalition forces, and sometimes, he treats the insurgents.

"He hasn't had a solid night's sleep since he left," Becky says. "I know he's not eating right." On the phone, Matt sounds tired and beat, says he's sick of it all.

The joy of his homecoming brings with it an undercurrent of new fears, namely post-traumatic stress syndrome. Will Matt be OK? Can he be happy?

Other military families have tried to prepare the Sirucheks, tell them what to watch for.

"I'm scared I'm not going to have the same brother," says Erik, "at least not for a while, if ever. I'm scared he's not going to want to do anything with me."

The Sirucheks have a block of rooms reserved outside Camp Lejeune, N.C.

Teachers and bosses have been put on notice. The last time they talked, Matt said his unit would be shipping out of Ramadi in days. He should be back in the States by Memorial Day weekend.

He told his dad to bring the black convertible.

A family's struggle to stay the course while one of their own is off in Iraq

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment